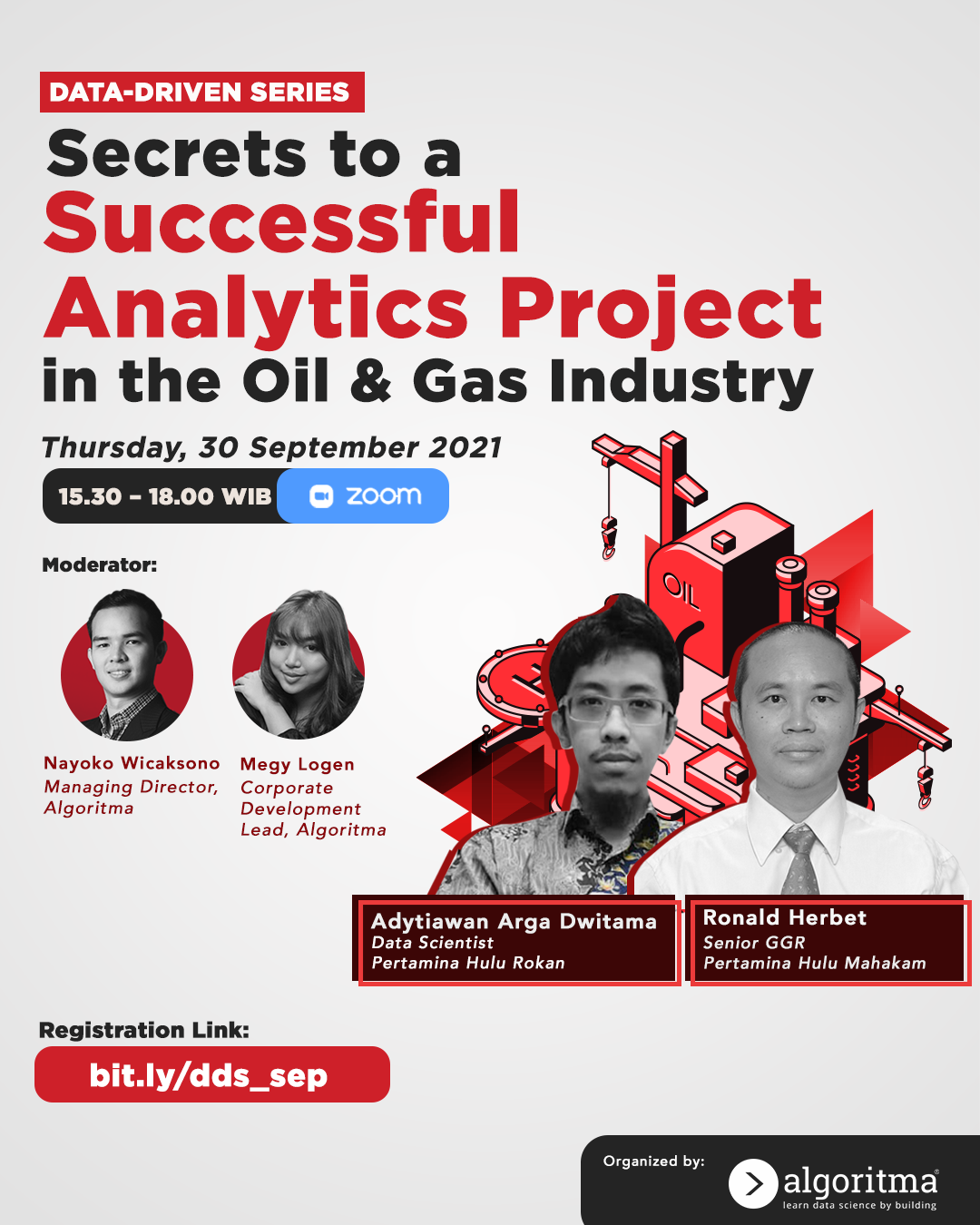

INTRODUCTION

One of many things to consider when we want to choose a machine learning model is the interpretability: can we analyze what variables or certain characteristics that contribute toward certain value of target variables? Some models can be easily interpreted, such as the linear or logistic regression model and decision trees, but interpreting more complex model such as random forest and neural network can be challenging. This sometimes drive the data scientist to choose more interpretable model since they need to communicate it to their manager or higher rank, who perhaps are not familiar with machine learning. The downside is, in general, interpretable model has lower performance in term of accuracy or precision, making them less useful and potentially dangerous for production. Therefore, there is a growing need on how to interpret a complex and black box model easily.

There exist a method called LIME, a novel explanation technique that explains the predictions of any classifier or regression problem in an interpretable and faithful manner, by learning an interpretable model locally around the prediction. By understanding on how our model works, we can have more advantage and could act wiser on what should we do.

On this article, we will explore how to implement LIME in regression problem.

LOCAL INTERPRETABLE MODEL-AGNOSTIC EXPLANATION (LIME)

LIME Characteristics

Let’s understand some of the LIME characteristic (Ribeiro et al., 2016)1:

- Interpretable

Provide qualitative understanding between the input variables and the response. Interpretability must take into account the user’s limitations. Thus, a linear model, a gradient vector or an additive model may or may not be interpretable. For example, if hundreds or thousands of features significantly contribute to a prediction, it is not reasonable to expect any user to comprehend why the prediction was made, even if individual weights can be inspected. This requirement further implies that explanations should be easy to understand, which is not necessarily true of the features used by the model, and thus the “input variables” in the explanations may need to be different than the features. Finally, the notion of interpretability also depends on the target audience. Machine learning practitioners may be able to interpret small Bayesian networks, but laymen may be more comfortable with a small number of weighted features as an explanation.

- Local Fidelity

Although it is often impossible for an explanation to be completely faithful unless it is the complete description of the model itself, for an explanation to be meaningful it must at least be locally faithful, i.e. it must correspond to how the model behaves in the vicinity of the instance being predicted. We note that local fidelity does not imply global fidelity: features that are globally important may not be important in the local context, and vice versa. While global fidelity would imply local fidelity, identifying globally faithful explanations that are interpretable remains a challenge for complex models.

- Model-Agnostic

An explainer should be able to explain any model, and thus be model-agnostic (i.e. treat the original model as a black box). Apart from the fact that many state of the art classifiers are not currently interpretable, this also provides flexibility to explain future classifiers.

How LIME Works

The generalized algorithm LIME applies is (Boehmke, 2018)2:

(1) Given an observation, permute it to create replicated feature data with slight value modifications.

(2) Compute similarity distance measure between original observation and permuted observations.

(3) Apply selected machine learning model to predict outcomes of permuted data.

(4) Select m number of features to best describe predicted outcomes.

(5) Fit a simple model to the permuted data, explaining the complex model outcome with m features from the permuted data weighted by its similarity to the original observation .

(6) Use the resulting feature weights to explain local behavior.

LIME package in R

You can implement LIME in R with lime package. See Thomas Lin Pederson’s3 github repository for more details.

To install the LIME package, you just simply run the install.packages() function.

install.packages("lime")

CASE STUDY

We will try to use black box model to solve regression problem and implement LIME to interpret how the model behave on various input. The dataset would be the Student Performance from UCI machine learning repository4. This data approach student achievement in secondary education of two Portuguese schools.

Library

The following library and setup will be used throughout the articles.

# Data Wrangling

library(tidyverse)

# Exploratory Data Analysis

library(GGally)

# Modeling and Evaluation

library(randomForest)

library(yardstick)

library(lmtest)

# Model Interpretation

library(lime)

# Set theme for visualization

theme_set(theme_minimal())

options(scipen = 999)

Import Data

Now we will import the dataset and inspect the contents. There are performances for 2 subjects: Mathematics and Portuguese language (language). For the first part, we will focus only on the math dataset.

df <- read.csv("data_input/student-mat.csv", sep = ";")

glimpse(df)

#> Rows: 395

#> Columns: 33

#> $ school <chr> "GP", "GP", "GP", "GP", "GP", "GP", "GP", "GP", "GP", "GP"…

#> $ sex <chr> "F", "F", "F", "F", "F", "M", "M", "F", "M", "M", "F", "F"…

#> $ age <int> 18, 17, 15, 15, 16, 16, 16, 17, 15, 15, 15, 15, 15, 15, 15…

#> $ address <chr> "U", "U", "U", "U", "U", "U", "U", "U", "U", "U", "U", "U"…

#> $ famsize <chr> "GT3", "GT3", "LE3", "GT3", "GT3", "LE3", "LE3", "GT3", "L…

#> $ Pstatus <chr> "A", "T", "T", "T", "T", "T", "T", "A", "A", "T", "T", "T"…

#> $ Medu <int> 4, 1, 1, 4, 3, 4, 2, 4, 3, 3, 4, 2, 4, 4, 2, 4, 4, 3, 3, 4…

#> $ Fedu <int> 4, 1, 1, 2, 3, 3, 2, 4, 2, 4, 4, 1, 4, 3, 2, 4, 4, 3, 2, 3…

#> $ Mjob <chr> "at_home", "at_home", "at_home", "health", "other", "servi…

#> $ Fjob <chr> "teacher", "other", "other", "services", "other", "other",…

#> $ reason <chr> "course", "course", "other", "home", "home", "reputation",…

#> $ guardian <chr> "mother", "father", "mother", "mother", "father", "mother"…

#> $ traveltime <int> 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 3, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 3, 1, 1…

#> $ studytime <int> 2, 2, 2, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 1, 1…

#> $ failures <int> 0, 0, 3, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 0…

#> $ schoolsup <chr> "yes", "no", "yes", "no", "no", "no", "no", "yes", "no", "…

#> $ famsup <chr> "no", "yes", "no", "yes", "yes", "yes", "no", "yes", "yes"…

#> $ paid <chr> "no", "no", "yes", "yes", "yes", "yes", "no", "no", "yes",…

#> $ activities <chr> "no", "no", "no", "yes", "no", "yes", "no", "no", "no", "y…

#> $ nursery <chr> "yes", "no", "yes", "yes", "yes", "yes", "yes", "yes", "ye…

#> $ higher <chr> "yes", "yes", "yes", "yes", "yes", "yes", "yes", "yes", "y…

#> $ internet <chr> "no", "yes", "yes", "yes", "no", "yes", "yes", "no", "yes"…

#> $ romantic <chr> "no", "no", "no", "yes", "no", "no", "no", "no", "no", "no…

#> $ famrel <int> 4, 5, 4, 3, 4, 5, 4, 4, 4, 5, 3, 5, 4, 5, 4, 4, 3, 5, 5, 3…

#> $ freetime <int> 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 4, 4, 1, 2, 5, 3, 2, 3, 4, 5, 4, 2, 3, 5, 1…

#> $ goout <int> 4, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 4, 4, 2, 1, 3, 2, 3, 3, 2, 4, 3, 2, 5, 3…

#> $ Dalc <int> 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1…

#> $ Walc <int> 1, 1, 3, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 3, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 4, 3…

#> $ health <int> 3, 3, 3, 5, 5, 5, 3, 1, 1, 5, 2, 4, 5, 3, 3, 2, 2, 4, 5, 5…

#> $ absences <int> 6, 4, 10, 2, 4, 10, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 4, 2, 2, 0, 4, 6, 4, 16…

#> $ G1 <int> 5, 5, 7, 15, 6, 15, 12, 6, 16, 14, 10, 10, 14, 10, 14, 14,…

#> $ G2 <int> 6, 5, 8, 14, 10, 15, 12, 5, 18, 15, 8, 12, 14, 10, 16, 14,…

#> $ G3 <int> 6, 6, 10, 15, 10, 15, 11, 6, 19, 15, 9, 12, 14, 11, 16, 14…

The dataset have more than 600 observations with 33 different variables. Our goal is to predict and explain the final score (G3) of each student using all available variables.

The full description of each variables are as follows:

- school - student’s school (binary: “GP” - Gabriel Pereira or “MS” - Mousinho da Silveira)

- sex - student’s sex (binary: “F” - female or “M” - male)

- age - student’s age (numeric: from 15 to 22)

- address - student’s home address type (binary: “U” - urban or “R” - rural)

- famsize - family size (binary: “LE3” - less or equal to 3 or “GT3” - greater than 3)

- Pstatus - parent’s cohabitation status (binary: “T” - living together or “A” - apart)

- Medu - mother’s education (numeric: 0 - none, 1 - primary education (4th grade), 2 – 5th to 9th grade, 3 – secondary education or 4 – higher education)

- Fedu - father’s education (numeric: 0 - none, 1 - primary education (4th grade), 2 – 5th to 9th grade, 3 – secondary education or 4 – higher education)

- Mjob - mother’s job (nominal: “teacher”, “health” care related, civil “services” (e.g. administrative or police), “at_home” or “other”)

- Fjob - father’s job (nominal: “teacher”, “health” care related, civil “services” (e.g. administrative or police), “at_home” or “other”)

- reason - reason to choose this school (nominal: close to “home”, school “reputation”, “course” preference or “other”)

- guardian - student’s guardian (nominal: “mother”, “father” or “other”)

- traveltime - home to school travel time (numeric: 1 - <15 min., 2 - 15 to 30 min., 3 - 30 min. to 1 hour, or 4 - >1 hour)

- studytime - weekly study time (numeric: 1 - <2 hours, 2 - 2 to 5 hours, 3 - 5 to 10 hours, or 4 - >10 hours)

- failures - number of past class failures (numeric: n if 1<=n<3, else 4)

- schoolsup - extra educational support (binary: yes or no)

- famsup - family educational support (binary: yes or no)

- paid - extra paid classes within the course subject (Math or Portuguese) (binary: yes or no)

- activities - extra-curricular activities (binary: yes or no)

- nursery - attended nursery school (binary: yes or no)

- higher - wants to take higher education (binary: yes or no)

- internet - Internet access at home (binary: yes or no)

- romantic - with a romantic relationship (binary: yes or no)

- famrel - quality of family relationships (numeric: from 1 - very bad to 5 - excellent)

- freetime - free time after school (numeric: from 1 - very low to 5 - very high)

- goout - going out with friends (numeric: from 1 - very low to 5 - very high)

- Dalc - workday alcohol consumption (numeric: from 1 - very low to 5 - very high)

- Walc - weekend alcohol consumption (numeric: from 1 - very low to 5 - very high)

- health - current health status (numeric: from 1 - very bad to 5 - very good)

- absences - number of school absences (numeric: from 0 to 93)

- G1 - first period grade (numeric: from 0 to 20)

- G2 - second period grade (numeric: from 0 to 20)

- G3 - final grade (numeric: from 0 to 20, output target)

Data Cleansing

We will cleanse the data so that all variables have proper type of data. For example, there are many integer variables that are actually categorical variables. All variables, except for G1, G2, G3, age, and absences will be tranformed into factors.

untransformed <- c("G1", "G2", "G3", "age", "absences")

df_clean <- df %>%

mutate_if(!(names(.) %in% untransformed), as.factor)

glimpse(df_clean)

#> Rows: 395

#> Columns: 33

#> $ school <fct> GP, GP, GP, GP, GP, GP, GP, GP, GP, GP, GP, GP, GP, GP, GP…

#> $ sex <fct> F, F, F, F, F, M, M, F, M, M, F, F, M, M, M, F, F, F, M, M…

#> $ age <int> 18, 17, 15, 15, 16, 16, 16, 17, 15, 15, 15, 15, 15, 15, 15…

#> $ address <fct> U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U, U…

#> $ famsize <fct> GT3, GT3, LE3, GT3, GT3, LE3, LE3, GT3, LE3, GT3, GT3, GT3…

#> $ Pstatus <fct> A, T, T, T, T, T, T, A, A, T, T, T, T, T, A, T, T, T, T, T…

#> $ Medu <fct> 4, 1, 1, 4, 3, 4, 2, 4, 3, 3, 4, 2, 4, 4, 2, 4, 4, 3, 3, 4…

#> $ Fedu <fct> 4, 1, 1, 2, 3, 3, 2, 4, 2, 4, 4, 1, 4, 3, 2, 4, 4, 3, 2, 3…

#> $ Mjob <fct> at_home, at_home, at_home, health, other, services, other,…

#> $ Fjob <fct> teacher, other, other, services, other, other, other, teac…

#> $ reason <fct> course, course, other, home, home, reputation, home, home,…

#> $ guardian <fct> mother, father, mother, mother, father, mother, mother, mo…

#> $ traveltime <fct> 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 3, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 3, 1, 1…

#> $ studytime <fct> 2, 2, 2, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 1, 1…

#> $ failures <fct> 0, 0, 3, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 0…

#> $ schoolsup <fct> yes, no, yes, no, no, no, no, yes, no, no, no, no, no, no,…

#> $ famsup <fct> no, yes, no, yes, yes, yes, no, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, y…

#> $ paid <fct> no, no, yes, yes, yes, yes, no, no, yes, yes, yes, no, yes…

#> $ activities <fct> no, no, no, yes, no, yes, no, no, no, yes, no, yes, yes, n…

#> $ nursery <fct> yes, no, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes,…

#> $ higher <fct> yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes…

#> $ internet <fct> no, yes, yes, yes, no, yes, yes, no, yes, yes, yes, yes, y…

#> $ romantic <fct> no, no, no, yes, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, y…

#> $ famrel <fct> 4, 5, 4, 3, 4, 5, 4, 4, 4, 5, 3, 5, 4, 5, 4, 4, 3, 5, 5, 3…

#> $ freetime <fct> 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 4, 4, 1, 2, 5, 3, 2, 3, 4, 5, 4, 2, 3, 5, 1…

#> $ goout <fct> 4, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 4, 4, 2, 1, 3, 2, 3, 3, 2, 4, 3, 2, 5, 3…

#> $ Dalc <fct> 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1…

#> $ Walc <fct> 1, 1, 3, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 3, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 4, 3…

#> $ health <fct> 3, 3, 3, 5, 5, 5, 3, 1, 1, 5, 2, 4, 5, 3, 3, 2, 2, 4, 5, 5…

#> $ absences <int> 6, 4, 10, 2, 4, 10, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 4, 2, 2, 0, 4, 6, 4, 16…

#> $ G1 <int> 5, 5, 7, 15, 6, 15, 12, 6, 16, 14, 10, 10, 14, 10, 14, 14,…

#> $ G2 <int> 6, 5, 8, 14, 10, 15, 12, 5, 18, 15, 8, 12, 14, 10, 16, 14,…

#> $ G3 <int> 6, 6, 10, 15, 10, 15, 11, 6, 19, 15, 9, 12, 14, 11, 16, 14…

Exploratory Data Analysis

The first thing we do before building the model is to do exploratory data analysis. The point is to find insight about the data before we start building the model.

Missing Values

We will check whether there are any missing values in the data.

df_clean %>%

is.na() %>%

colSums()

#> school sex age address famsize Pstatus Medu

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> Fedu Mjob Fjob reason guardian traveltime studytime

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> failures schoolsup famsup paid activities nursery higher

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> internet romantic famrel freetime goout Dalc Walc

#> 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

#> health absences G1 G2 G3

#> 0 0 0 0 0

No missing data found in any variables, so we are good to go.

Correlation Between Variables

We will try to find the correlation between numeric variables.

ggcorr(df_clean, label = T)

The final score (G3) has strong correlation with the score of the first (G1) and second period (G2). This is not surprising, since student achievement is highly affected by previous performances. Based on the author’s commentary on this topic5, it is more difficult to predict G3 without G2 and G1. We will try to prove this point.

Influence of Schools

Since the data are collected from 2 different schools, we would like to see if there is a great discrepancy in the final score between school.

df_clean %>%

mutate(school = ifelse(school == "GP", "Gabriel Pereira (GP)", "Mousinho da Silveira (MS)")) %>%

ggplot(aes(G3, fill = school)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.6, show.legend = F) +

facet_wrap(~school) +

labs(x = NULL,

title = "Final Score Distribution of Different Schools")

Based on the density plot, the final score distribution of math are almost similar in both school. Thus, schools might not be a strong predictor for the final score of a student.

Cross-Validation

Now that we’ve explore some insight from our data, we will start to split the data into training set and testing set, with 80% of the data will be the training set.

set.seed(123)

df_row <- nrow(df_clean)

index <- sample(df_row, 0.8*df_row)

data_train <- df_clean[ index, ]

data_test <- df_clean[ -index, ]

Model Fitting and Evaluation

Linear Regression

As a common practice, we will build the basic linear regression model to fit the data.

model_linear <- lm(G3 ~ . , data = data_train)

We will use stepwise approach to find a linear model with minimum AIC.

model_step <- step(model_linear, direction = "both", trace = 0)

summary(model_step)

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = G3 ~ age + failures + activities + romantic + famrel +

#> absences + G1 + G2, data = data_train)

#>

#> Residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -8.7011 -0.5239 0.2289 0.9347 3.3135

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

#> (Intercept) 2.221332 1.544307 1.438 0.151356

#> age -0.222564 0.085415 -2.606 0.009623 **

#> failures1 -0.821324 0.298484 -2.752 0.006288 **

#> failures2 -0.642575 0.499468 -1.287 0.199247

#> failures3 -0.387404 0.625616 -0.619 0.536227

#> activitiesyes -0.418825 0.196670 -2.130 0.034014 *

#> romanticyes -0.348120 0.216439 -1.608 0.108793

#> famrel2 -1.194241 0.824513 -1.448 0.148537

#> famrel3 0.003406 0.711698 0.005 0.996185

#> famrel4 0.295796 0.680765 0.435 0.664232

#> famrel5 0.552679 0.696697 0.793 0.428235

#> absences 0.048852 0.012578 3.884 0.000126 ***

#> G1 0.133187 0.057151 2.330 0.020442 *

#> G2 0.975842 0.051338 19.008 < 0.0000000000000002 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Residual standard error: 1.731 on 302 degrees of freedom

#> Multiple R-squared: 0.8581, Adjusted R-squared: 0.852

#> F-statistic: 140.5 on 13 and 302 DF, p-value: < 0.00000000000000022

The model has an Adjusted R-Squared of 85%, suggesting that the model can explain the data well enough. We might also interested in seeing how good the model will be on the testing dataset.

# Function for evaluating model

eval_recap <- function(truth, estimate){

df_new <- data.frame(truth = truth,

estimate = estimate)

data.frame(RMSE = rmse_vec(truth, estimate),

MAE = mae_vec(truth, estimate),

"R-Square" = rsq_vec(truth, estimate),

check.names = F

) %>%

mutate(MSE = sqrt(RMSE))

}

pred_test <- predict(model_step, data_test)

eval_recap(truth = data_test$G3,

estimate = pred_test)

#> RMSE MAE R-Square MSE

#> 1 2.326917 1.55557 0.7727604 1.525424

The linear model seems satisfying enough for us. However, our goal is to explain how each predictor will influence the result (target variable). In order to get unbiased estimator for the linear model, we should check if the linear model satisy it’s own assumption. Any violation in the model assumption will make the estimate coefficient and the test result unreliable/biased6.

Residuals Normality

First, we will check whether the residuals are normally distributed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

$$ H_0 : p-value > 0.05 : Residuals\ Normally\ Distributed \

H_1 : p-value < 0.05 : Residuals\ Are\ Not\ Normally\ Distributed $$

shapiro.test(model_step$residuals)

#>

#> Shapiro-Wilk normality test

#>

#> data: model_step$residuals

#> W = 0.79108, p-value < 0.00000000000000022

Based on the result, the residuals are not normally distributed.

Residuals Autocorrelation

Second, we will check whether the residuals are correlating with itself using the Durbin-Watson test.

$$ H_0 : p-value > 0.05 : Residuals\ Are\ Not\ Autocorrelated \

H_1 : p-value < 0.05 : Residuals\ Are\ Autocorrelated $$

dwtest(model_step)

#>

#> Durbin-Watson test

#>

#> data: model_step

#> DW = 1.8459, p-value = 0.08874

#> alternative hypothesis: true autocorrelation is greater than 0

Based on the test, the residuals are also contain autocorrelation

Homoscesdasticity

Homoscesdasticity means that the variance of the random variables are constant. We can use the Breusch-Pagan test to check the homoscesdasticity of the model.

$$ H_0 : p-value > 0.05 : Constant\ Variance\ (Homoscesdasticity) \

H_1 : p-value < 0.05 : Variance\ Not\ Constance\ (Heterocesdasticity) $$

bptest(model_step)

#>

#> studentized Breusch-Pagan test

#>

#> data: model_step

#> BP = 43.801, df = 13, p-value = 0.0000331

The model is also doesn’t have a constant variance.

Multicollinearity

The multicollinearity will look for a high correlation between predictors.

rms::vif(model_step)

#> age failures1 failures2 failures3 activitiesyes

#> 1.203030 1.210549 1.114074 1.142246 1.019727

#> romanticyes famrel2 famrel3 famrel4 famrel5

#> 1.116431 2.828425 6.882270 12.218073 10.286541

#> absences G1 G2

#> 1.103045 3.790568 3.842387

No strong multicollinearity are presence since all predictors have VIF < 10.

So … our model failed to fulfill almost all of assumptions for linear regression model. The interpretation of the estimate coefficient and the significant test would be unreliable. You might be interested in tuning the linear model to fulfill the assumption but for now, we will proceed to use more advanced models: Random Forest and Support Vector Regression (SVR).

Random Forest

Random Forest implementation come in many packages but for this post I will use randomForest() from randomForest package.

set.seed(123)

model_rf <- randomForest(x = data_train %>% select(-G3),

y = data_train$G3,

ntree = 500)

model_rf

#>

#> Call:

#> randomForest(x = data_train %>% select(-G3), y = data_train$G3, ntree = 500)

#> Type of random forest: regression

#> Number of trees: 500

#> No. of variables tried at each split: 10

#>

#> Mean of squared residuals: 3.414625

#> % Var explained: 83.08

We will evaluate the Random Forest model.

pred_test <- predict(model_rf, data_test, type = "response")

eval_recap(truth = data_test$G3,

estimate = pred_test)

#> RMSE MAE R-Square MSE

#> 1 2.006828 1.412788 0.8400051 1.416626

The Random Forest is slightly better than the linear model.

Support Vector Regression (SVR)

SVR is a variant of Support Vector Machine for regression problem7. If you are interested in SVM, you can the article from algotech8. The SVM implementation can be acquired from the e1071 package.

library(e1071)

model_svr <- svm(G3 ~ ., data = data_train)

pred_test <- predict(model_svr, data_test)

eval_recap(truth = data_test$G3,

estimate = pred_test)

#> RMSE MAE R-Square MSE

#> 1 2.3571 1.447381 0.776828 1.535285

The SVR model has lower performance compared to Random Forest. However, we will still use both model for further analysis both as comparison and as examples.

MODEL INTERPRETATION

You can actually find the importance of variables in Random Forest. The importances are calculated using the Gini index.

model_rf$importance %>%

as.data.frame() %>%

arrange(-IncNodePurity) %>%

rownames_to_column("variable") %>%

head(10) %>%

ggplot(aes(IncNodePurity,

reorder(variable, IncNodePurity))

) +

geom_col(fill = "firebrick") +

labs(x = "Importance",

y = NULL,

title = "Random Forest Variable Importance")

However, variable importance measures rarely give insight into the average direction that a variable affects a response function. They simply state the magnitude of a variable’s relationship with the response as compared to other variables used in the model. We can’t know specifically the influence of each factors for a single observation (no local-fidelity). That’s why we need LIME to help us understand individually what influence the performance of each student.

Now we will try to interpret the black box model using lime.

Explainer

The first thing to is to build an explainer. This explainer object will be used as the foundation to interpret the black box model.

set.seed(123)

explainer <- lime(x = data_train %>% select(-G3),

model = model_rf)

Some parameter you can adjust in lime function:

x= Dataset that is used to train the model.model= The machine learning model we want to explainbin_continuous= Logical value indicating if numerical variable should be binned into several groupsn_bins= Number of bins for continuous variables

Explanation

The next thing to do is to build the explanation for each data test. The explanation will give the interpretation of the model toward each observation. However, in these part we will only make explanation for the first 4 observation of the data for simplicity.

# Select only the first 4 observations

selected_data <- data_test %>%

select(-G3) %>%

slice(1:4)

# Explain the model

set.seed(123)

explanation <- explain(x = selected_data,

explainer = explainer,

feature_select = "auto", # Method of feature selection for lime

n_features = 10 # Number of features to explain the model

)

#> Error: The class of model must have a model_type method. See ?model_type to get an overview of models supported out of the box

The explanation gave us an error. If you don’t face the same error, congratulations, you can proceed to visualize the explanation using the plot_features() function below. However, I will explain how to handle the error first.

plot_features(explanation)

Troubleshooting Error in model_type

The error happened because lime didn’t recognize the model. To handle this, we first specify the model so that it can be recognized by lime.

First, check the class of the model.

class(model_rf)

#> [1] "randomForest"

The class of our Random Forest model is randomForest.

The second step is to create a function named model_type. followed by the class of the model. In our model, the class is “randomForest”, so we need to create a function named model_type.randomForest. Since the problem is a regression problem, the function must return “regression”.

model_type.randomForest <- function(x){

return("regression") # for regression problem

}

We also need a function to store the prediction value. Same with the model_type., we need to create a predict_model. followed by the class of our model. The function would be predict_model.randomForest. The content of the function is the function to predict the model. In Random Forest, the function is predict(). We need to return the prediction value and convert them to data.frame, so the content would be predict(x, newdata) to return the probability of the prediction and convert them with as.data.frame().

predict_model.randomForest <- function(x, newdata, type = "response") {

# return prediction value

predict(x, newdata) %>% as.data.frame()

}

Now once again we will run the previous explanation. The n_features determine how many features that will be used for interpretation. Here, we will only consider of 10 features. You can choose another number if you wish. The feature_select parameter will determine how the lime select which features/predictors that will be used for interpreting the model. To consider all predictors, you can simply change the parameter to feature_select = "none" to indicate that all features will be considered and there are no selection.

set.seed(123)

explanation <- explain(x = selected_data,

explainer = explainer,

n_features = 10, # Number of features to explain the model

feature_select = "auto", # Method of feature selection for lime

)

Visualization and Interpretation

Finally, we will visualize the explanation using the plot_features() function.

plot_features(explanation = explanation)

The case indicate the index of the data. Case : 1 indicate the first observation, Case : 2 indicate the second observation, etc. The prediction value show the predicted value based on the model interpretation and prediction. You can compare the prediction value with the actual final score (G3) value.

head(data_test$G3)

#> [1] 6 10 15 16 14 10

Inside the plot, we can see several bar charts. The y-axis show the features while the x-axis show the relative strength of each features. The positive value (blue color) show that the feature support or increase the value of the prediction, while the negative value (red color) has negative effect or decrease the prediction value.

Each observation has different explanation. For the first observation, The G2 and G1 value has negative effect toward the final score (G3). The interpretation is that because the G2 (score of the student during the second grade) is lower than 9 and G1 (score of the student during the first grade), it will lower the predicted final score (G3). However, since the student never fail in the past class (failure = 0), it increase the predicted final score, although only by little value.

The second observation is almost similar with the first observation. Since the student has low G1 and G2, the predicted final score will be low. However, this student also has failed 3 times in the past (failure = 3), the predicted is also lowered down.

The third observation has a quite good G1 (G1 < 13) and G2 (G2 < 13) and never failed in the past classes, so he/she has higher predicted final score. The fourth observation has almost the same characteristics with the third observation.

As we can see, the student’s performance during the first and second grade (G1 & G2) strongly affect the final score of each student, followed by the number of past failure (failure), number of school absences (absences) and the motivation to take higher education (higher) for the first 4 observations of the data test.

The next element is Explanation Fit. These values indicate how good LIME explain the model, kind of like the \(R^2\) (R-Squared) value of linear regression. Here we see the Explanation Fit only has values around 0.50-0.7 (50%-70%), which can be interpreted that LIME can only explain a little about our model. You may consider not to trust the LIME output since it only has low Explanation Fit.

Tuning LIME

You can improve the Explanation Fit by tuning the explain function parameter. The following parameter increase the explanation fit up to 90%. You can adjust the value of each parameters until you’ve found the desired explanation fit.

set.seed(123)

explanation <- explain(x = selected_data,

explainer = explainer,

dist_fun = "manhattan",

kernel_width = 2,

n_features = 10, # Number of features to explain the model

feature_select = "auto", # Method of feature selection for lime

)

plot_features(explanation)

Some parameters you can adjust in explanation function:

x= The object you want to explainexplainer= the explainer object from lime functionn_features= number of features used to explain the datan_permutations= number of permutations for each observation for explanation. THe default is 5000 permutationsdist_fun= distance function used to calculate the distance to the permutation. The default is Gower’s distance but can also use euclidean, manhattan, or any other distance function allowed by ?dist()kernel_width= An exponential kernel of a user defined width (defaults to 0.75 times the square root of the number of features) used to convert the distance measure to a similarity value

Now the important features are changed along with the increasing explanation fit. The G2 variable is still the most important feature for all observation while G1 has declined.

Similarly, you can create the explanation for the SVR model.

set.seed(123)

explainer <- lime(x = data_train %>% select(-G3),

model = model_svr)

Check the class of SVR model.

class(model_svr)

#> [1] "svm.formula" "svm"

Create SVR model specification for lime.

model_type.svm <- function(x){

return("regression") # for regression problem

}

predict_model.svm <- function(x, newdata, type = "response") {

# return prediction value

predict(x, newdata) %>% as.data.frame()

}

Create explanation and visualize the result.

set.seed(123)

explanation <- explain(x = selected_data,

explainer = explainer,

feature_select = "auto", # Method of feature selection for lime

n_features = 10 # Number of features to explain the model

)

plot_features(explanation)

REFERENCE

- Ribeiro, M. Tulio, Singh, Sameer, and Guestrin, Carlos. 2016. “Why Should I Trust You?”: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. [return]

- Brad Boehmke. 2018. “LIME: Machine Learning Model Interpretability with LIME”. [return]

- Thomas Lin Pederson. “Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (R port of original Python package)”. [return]

- Student Performance Data Set. [return]

- P. Cortez and A. Silva. Using Data Mining to Predict Secondary School Student Performance. In A. Brito and J. Teixeira Eds., Proceedings of 5th FUture BUsiness TEChnology Conference (FUBUTEC 2008) pp. 5-12, Porto, Portugal, April, 2008, EUROSIS, ISBN 978-9077381-39-7. [return]

- What Happens When You Break the Assumptions of Linear Regression? [return]

- EDUCBA. Support Vector Regression. [return]

- Efa Hazna Latiefah. Support Vector Machine [return]

More details

More details More details

More details

Share this post

Twitter

Facebook

LinkedIn